Matthew J. Milliner on Makoto Fujimura

At the end of the last century, somewhere in lower Manhattan, I first stepped into one of Makoto Fujimura’s early studios where I was welcomed with undeserved hospitality. I was a college student in love with art history, and the buzz was that there was actually an artist—a very good one—who dared to be a person of faith and still be an artist. It sent a frisson of excitement through the ranks of those who were part of the art conversation who happened to be persons of faith. Then there was a risk that bringing up such topics would get you in trouble. Then there was a sense that faith was forbidden. And that was all so long ago.Everything is different now. If, in 1979, Rosalind Krauss famously said, “we find it indescribably embarrassing to mention art and spirit in the same sentence,” today many of us find it indescribably embarrassing not to.

It is hard to identify a single turning point. Maybe it was when the Visual Commentary on Scripture was launched from London’s Tate Modern in 2018. Maybe it was when Thomas Crow published No Idols: The Missing Theology of Art (2017). Perhaps it was the Hilma af Klint show at the Guggenheim (2018-19). Or was it the way that the fresh embrace of African American art finally opened the drawbridge for religion like never before? Maybe it was just that major art historical treatments of modern and contemporary art that re-incorporate religion were finally penned, whether Jeffrey Kosky’s Arts of Wonder (2012), Charlene Spretnak’s The Spiritual Dynamic in Modern Art (2014), or Anderson and Dyrness’s Modern Art and the Life of a Culture (2016). Maybe it was S. Brent Plate’s 2017 Los Angeles Review of Books article, “Reports of the Death of Religious Art Have Been Greatly Exaggerated.” Or was it the 2019 launch of Bridge Projects in the heart of Los Angeles, a gallery created to facilitate such conversations? At its opening show, Michael Govan, director of LACMA, announced, “I guess if you’re from California you’re allowed to talk about it” (the “it” being serious spirituality). Then again, maybe the turning point was the 2020 publication of Fujimura’s Art + Faith by Yale University Press.

Almost as if to challenge the future-focused Marxism that held together the mainstream art world’s old secular order, Art + Faith is future focused as well. Fujimura points out that the word kainos in the Greek New Testament means perpetually or eternally New, and he believes the “New is breaking into the old, broken earth.” Artmaking, or really making of any kind, is therefore a step along the “journey toward the New.” For Fujimura, “The Good News is that heaven will come to us to resurrect our decaying bodies and earth too, in mysterious ways….” In the creation to come, even our artistic efforts might find themselves taking on new forms.

For Fujimura, it is the humble wounds of Christ (still marking his resurrected body) that offer a bridge from this creation to the next. Fujimura is keen to mark the unique features of Christian eschatology insofar as it pertains to artmaking. As if to prove his point, Fujimura has been joined in this effort by a new volume published this year, edited by Jeremy Begbie, Daniel Train and W. David O. Taylor, entitled The Art of New Creation: Trajectories in Theology and the Arts. For Begbie as for Fujimura, art finds itself inhabiting the space between “God’s first ‘Let there be!’” and the “glittering finale of a world remade.”As my small contribution to this exciting trajectory, I will pick up on connections made by Fujimura’s earlier book Silence and Beauty (2016), where he explored the subtle (and eventually suppressed) intersections of Christian faith and Buddhism at Daitoku-ji monastery in Kyoto. Even if Buddhism is not referred to in Art + Faith, these connections can still be pursued. Indeed, Art + Faith reminds me of the Jesus Sutras (Jingjiao Documents), Chinese Christian texts discovered at the “Cave of the Thousand Buddhas” (Mogao Caves) in the last century, but which are at least 1000 years old.

These documents emerged from the unique interaction between Buddhism, Christianity and Taoism in the Tang dynasty (618-907AD). In one remarkable passage from the Jesus Sutras, Buddhist enlightenment appears to be pictured as a “bejeweled mountain with groves of jade and pearl-like fruit that glistened and cast light in the forest.” But (as anyone who has tried meditating over a period of years will know), “the mountain was high, the road was long.” Jesus, “the Good Spiritual Friend,” however, “makes ladders and cut steps in the mountain.” This is one of the most unexpected and beautiful articulations of Christian faith of which I am aware.

The Mogao Caves (“Cave of the Thousand Buddhas”) at Dunhuang in The Gansu Province, China (photo: Leon Petrosyan)

Wonderful as that passage may be, however, another one especially bears on Fujimura’s project. Perhaps it is some kind of response to the famous Heart Sutra, among the most representative of classic Buddhist texts. The Heart Sutra reads: “The Bodhisattva Avolokita, while moving in the deep course of Perfect Understanding, shed light on the Five Skandhas [material and mental loci of attachment] and found them equally empty. After this penetration, he overcame ill-being.” The Jesus Sutras, however, take a different approach: “When heaven and earth come to an end, the souls of the dead will come back to life through the five skandhas…. the five skandhas will ensure that it can live permanently in the world.” In short, both faiths agree upon the limitations of the senses, but differ in regard to their eventual renewal in the New Creation to come.

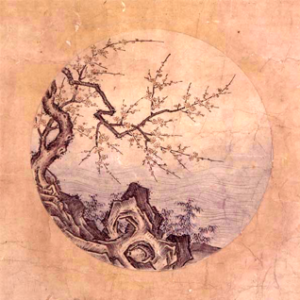

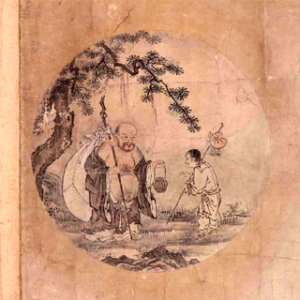

There is also a moment from within the history of Buddhism that Art + Faith brought to mind. The ox-herding pictures, a magnificent parable of enlightenment, are a well-known encapsulation of Ch’an Buddhism, which would become Zen Buddhism when it arrived in Japan. In the most famous of these drawings, the 12th century Chinese Zen master Kakuan Shien added commentaries to these illustrations, of which some faithful copies survive.

Pictures 8 (the former conclusion) and the additions of 9 and 10 to the Ox-Herding series

What is astonishing about Kakuan’s series of ox-herding pictures, however, is that unlike his predecessors, he did not conclude the series with the blank circle of enlightenment. Instead, he added two additional drawings, which Addison Hodges Hart, in his book The Ox-Herder and the Good Shepherd, calls “a world-affirming, crowning picture to conclude the set.” Which is to say, instead of ending the series in formless bliss, the enlightened ox-herder—for Kakuan at least—is plunged back into creation, back into the five skandhas. Which is to say, even after enlightenment, creation still matters.

Of course, this can be understood within Buddhism as the ideal of the boddhisatva, who vows to save all sentient beings, who proclaims, in Kakuan’s words: “I am found in the company of winebibbers and fishmongers, and they all become enlightened.” But after reading Fujimura’s Art + Faith, with its focus on the New Creation, I cannot help but think that Kakuan’s addition to the ox-herder series might also be understood, as with the Jesus Sutras, to be one more example of a need to affirm not only the present order, but a creation yet to come as well.

Convergences like this between Christianity and Buddhism require substantial theological and spiritual claims, which is more than the mainstream art world on its own can provide. I find the unexpected overlap between living spiritual traditions, their fruitfully conflicting integrities, fascinating. The fact that the art world is increasingly open to such conversations, which transcend mere aesthetic or political considerations, makes me think I’m not alone.

Matthew J. Milliner is associate professor of art history at Wheaton College, and the author of The Everlasting People(2021) and Mother of the Lamb: The Story of a Global Icon (2022).