Avery Robinson

In 1895, Adolf Ágai wrote an article in the Jewish weekly Egyenlőség (Equality) in which he waxes rhapsodic about Jewish foods. Ágai (1836–1916)—one of the most popular Hungarian Jewish editors, satirists, and journalists of the fin-de-siècle—seems to offer a late-nineteenth century version of “bagel and lox Judaism.” His paean to the Jewish kitchen longingly describes traditional dishes—a variety of cholents and kugels, ganef (kugel’s primordial cousin, a simple cholent dumpling)—and kosher versions of Hungarian dishes, such as vadas nyúl, hare cooked in a cream sauce that evolved into an “Easter lamb” cooked in an “emulsion of almonds” playing in for the sour cream.

Less than a year later, Egyenlőség editor Samu Haber (1865–1922) published his own reflections on Hungarian Jewish foods, extolling “the cult of cholent,” describing the dish’s popularity among non-Jewish Hungarians dining on Budapest’s posh Andrássy Boulevard. Beyond the non-Jewish adoration for Ashkenazi Sabbath stews (sold in restaurants outside of Hasidic enclaves!), Haber lauds ganef, apple kugel, fish cooked in a walnut sauce, and flódni (a pastry that has become symbolic of 21st-century Hungarian Jewry), among other Jewish Hungarian foods. Haber, like Ágai, goes on ad appetitus.

The poetic joy that Ágai and Huber express for Jewish foods is contagious. Reading these passages about iconic Jewish dishes may very well cause one’s stomach to rumble and mouth to water, so naturally, one ought to know: how do I make these dishes? And where can I find a reputable recipe?

Fortunately for us, Andras Koerner has undertaken the colossal task of recording and describing culinary histories and cultural practices from the vibrant Jewish communities that once thrived in Hungary and were nearly wiped out in World War II and then largely neglected under communism. Indeed, his Jewish Cuisine in Hungary: A Cultural History with 83 Authentic Recipes (2019) won a Jewish Book Award for its thorough sociological treatment of Jewish Hungarian foodways. Among this book’s many treasures is its survey of nineteenth- and twentieth-century Hungarian Jewish cookbooks.

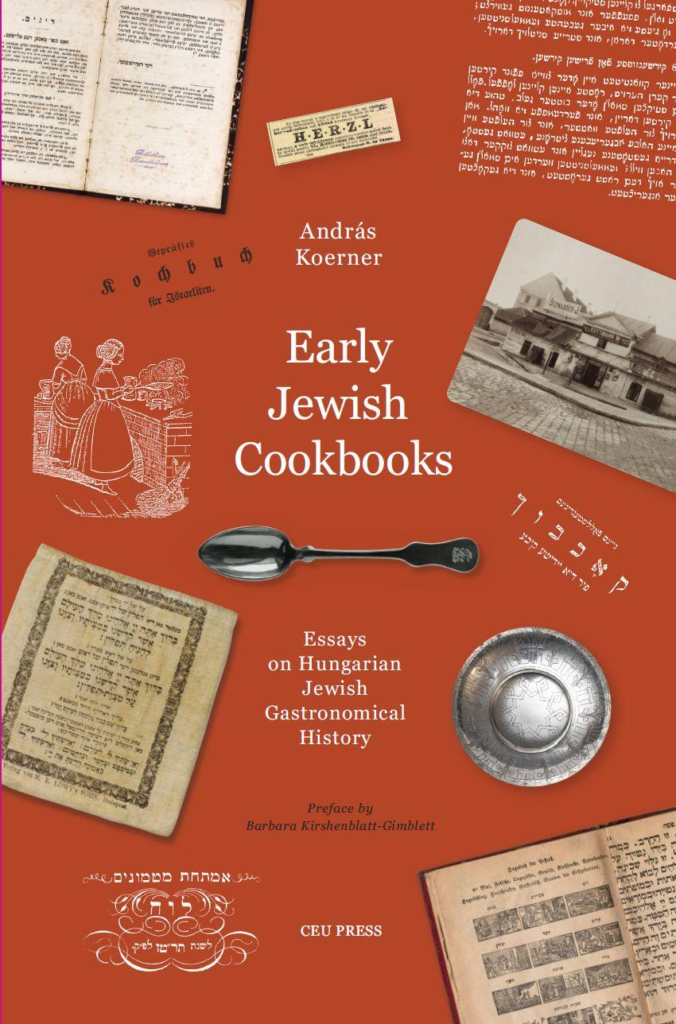

In Early Jewish Cookbooks, Koerner continues his comprehensive exposition with a deeper look at some of Hungary’s more historically significant Jewish cookbooks, focusing on the publishers, sociological circumstances, and novel editorial choices. With a preface by Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, the leading authority on early Jewish cookbooks, the reader is assured that this book is intellectually and critically thorough. And if that isn’t enough, Kirshenblatt-Gimblett’s tone echoes the joy that Koerner himself expresses, indicating that you too will have enjoy your journey into Hungarian Jewish cookbooks; this adventure begins with the least-known and perhaps most peculiar text, Nayes folshtendiges kokhbukh fir di yidishe kikhe (A New and Complete Cookbook of the Jewish Cuisine, 1854). Published in Pest by M. E. Löwys Sohn and printed in Vienna, this book is the first cookbook ever printed in Hebrew characters.

Surprisingly, perhaps, this book was written neither in Hebrew nor Yiddish (which uses Hebrew characters like all Jewish languages), but in Judeo-Deutsch. Its headings and titles are printed in a square Hebrew font while the body of the text is printed in vaybertaytsh, a cursive typeface associated with the Tsene rene and other Yiddish texts marketed to Ashkenazic women that was popular from the sixteenth to mid-nineteenth centuries. It is unclear why Markus Löwy published this book in Hebrew characters when German Jewish cookbooks were rather successful, but his use of vaybertaytsh suggests he was marketing this book to an emergent middle-class Jewish woman, a consumer who was much more comfortable reading Hebrew characters than any other language.

Jewish women in the Habsburg Empire in the first half of the nineteenth century were much more literate in Yiddish and Hebrew than in German or Hungarian. For more than fifty years before the publication of Nayes folshtendiges kokhbukh, Jews in Hungary increasingly fell under the spell of the Haskalah, which advocated for cultural and linguistic reform. This Jewish Enlightenment, identified most closely with Moses Mendelssohn (who famously authored a German translation of the Bible in Hebrew characters in 1780–83), drew people from their “backwards” Yiddish “jargon” toward German language, culture, and identity.

The acculturating forces of the Haskalah brought people from small town and village life into a modern, urban environment, uprooting centuries of tradition. In the pre-modern world, women learned to cook from their mothers and grandmothers. As with other domestic skills, this gendered-female labor was passed down through repetition and guidance from generation to generation. For centuries, this slowly evolving vernacular folk wisdom remained relatively stable. However, in the past 500 years, foodways experienced an exponentially quicker rate of change, reflecting an increasingly global and upwardly mobile environment.

The transformation of many European kitchens, which were often simple wood-fueled hearths in the medieval period, became most visible in the way people ate. For millennia, earthenware was dominant, and in the west, the only eating utensils were spoons and knives. In the past 500 years, it became more common for people to have multiple metal pots, forks (!), and even enclosed ovens in their own homes. In addition to these technological advances, ingredients changed, too. Notably for the Hungarian kitchen, New World ingredients—e.g., potatoes, tomatoes, chocolate, paprika chiles, and inexpensive sugar—became increasingly popular, available, and affordable. Within this turbulent and exciting period, many Jewish women moved to cities that were distant (culturally and geographically) from generational culinary knowledge. Nonetheless, and without mom or bubbe on speed-dial, they still needed to cook. In this new environment, it appears that many aspired to serve new, different (middle-class) foods, not the simple porridges and open-faced rye bread sandwiches from their childhood.

Recognizing this need, in 1815, Joseph Stolz, the private chef of the Grand Duke of Baden, published the first ever Jewish cookbook in Karlsruhe, Germany. In the introduction to Kochbuch für Israeliten (Cookbook for Jews), Stolz, who was not Jewish, explained that he “gladly assented to the frequently repeated requests of educated Jews” to print his manuscript. Curiously, perhaps, this ur-Jewish cookbook contained zero Jewish recipes. Instead, the book consisted primarily of German foods adapted to the laws of kashrut. The recipes in Stolz’s book neither mixed dairy and meat, nor contained otherwise forbidden ingredients. Though this is explicitly and deliberately a Jewish cookbook, it is only incidentally so by modern conventions of Jewish culture because of the absence of culturally/ethnically Jewish recipes. That is to say, there are no recipes for cholent, kugel, ganef, flódni, matzah, gefilte fish, or any other Ashkenazi dishes.

Fortunately, in 1835, Rahel Aschmann blessed German Jewry with the publication of Geprüftes Kochbuch für Israeliten (Tested Cookbook for Jews), which had the distinct honor of being the first Jewish cookbook to include explicitly Jewish and also Hungarian recipes. Koerner describes this text as a segue to the third-ever published Jewish cookbook, Julie Löv’s Die Wirthschaftliche israelitsche Köchin (The Thrifty Jewish Cook, 1840), published in Pozsony (today, Bratislava, Slovakia).

Always in conversation with his previous research, Koerner acknowledges, while nothing “can diminish Julie Löv’s achievement of publishing the first Jewish cookbook in Hungary, today I am a little less enthusiastic about her work [ . . . ] because it has become obvious that Löv copied nearly all the recipes from [Aschmann’s cookbook].” Continuing his analysis of Hungarian cookbooks published before 1945, Koerner points out which recipes Löv copied from pre-existing texts. In doing so, Koerner demonstrates an encyclopedic knowledge of German- and Hungarian-language cookbooks as well as those written in various regional dialects, as evidenced in his study of the 1938 WIZO cookbook from Lugoj (Romania), which gleaned heavily from Mrs. Márton Rosenfeld’s 1927 cookbook published in Subotica (then in Yugoslavia, today Serbia).

Though this overt, rampant plagiarism and lack of creativity may be disheartening, one must remember that published cookbooks generally reflect the aspirational tendencies of authors, publishers, and consumers. This is to say, these cookbooks may not include the foods people are actually eating. Think of your newest cookbook—perhaps that new Israeli one your friends were so excited to buy—and ask yourself, how often do you use it? Is it really a workaday recipe book giving you direction for weekday meals, Shabbat dinners and lunches, and all holidays? Do you rely on this to feed your family day in and day out, entertain guests, and celebrate the calendar? Or do you principally use it for a handful of recipes (if that), relying instead on your own creativity or muscle memory to get you through your week?

Many nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Jewish cookbooks serve to preserve (or create) Jewish tradition. Many of these books, such as Therese Lederer’s excellent Koch-Buch für israelitche Frauen (Cookbook for Jewish Women; Budapest, 1876) do include a number of traditional Hungarian and Ashkenazic Jewish dishes. For example, Lederer’s 1876 print includes cholent, sixteen kinds of strudel, a handful of kugels, chremsel (a Passover fritter), and barches (German challah). By 1884, this book had been printed in five revised editions. And in 1892, it was translated into Dutch, preceding Sara Vos’ Oorspronkelijk Israëlitsch Kookboek (Amsterdam, 1894), the first Dutch Jewish cookbook that was not a translation.

In contrast to published cookbooks, individually-compiled recipe collections often provide a clearer window into both the quotidian and festival tables of people and families. It is with this in mind that Koerner returns to his great-grandmother Teréz Berger’s manuscript cookbook, which she started recording in her mother’s kitchen in 1869. This untitled treasure, handwritten in German by Berger (1851–1938) over the course of sixty years, is the basis of Koerner’s A Taste of the Past; The Daily Life and Cooking of a 19th-Century Hungarian Jewish Homemaker (2004), a nearly 400-page culinary record combining personal memories from multiple generations of family and friends with letters, culinary ephemera, and recipes to reconstruct Berger’s middle-class Jewish life in western Hungary and her final years in interwar Budapest.

In Early Jewish Cookbooks, Koerner digs deeper into Berger’s life, putting her foodways into conversation with contemporaneous published and manuscript cookbooks to understand why, for example, her recipes rarely include paprika and why garlic, the stereotypical flavor of European Jewish food, is entirely absent. He explains her sweet-tooth, peculiarly reflected in her recipe for kohlrabi, one of the three vegetable dishes she includes in her handwritten collection, and one of the most popular vegetables in the Hungarian kitchen. Berger braises the kohlrabi in a pan with goose fat and onion that is “seasoned” with sugar before adding meat stock and—more sugar. It seems that Jewish Hungarians—presumably like most Jews living west of the Gefilte Line, have a strong predilection for sweets, i.e., noodles and cottage cheese with sugar sprinkled on top, sauteed cabbage, sweet noodle kugel, and apparently, caramel braised kohlrabi. Raised in a “culturally assimilated, but strictly observant family,” Berger “maintained a traditional Jewish household” after her marriage. It is reassuring to see that over a hundred years ago, maintaining a kosher/traditional home did not deter people from eating the delicious foods of their neighbors (e.g., pizza, sushi, and goose schmaltz-braised kohlrabi).

In addition to his thorough examination of cookbooks as a lens into the domestic practices (and aspirations) of Jews in Hungary, Koerner also shares important insights into the public experience of Hungarian Jewish food, principally through Budapest’s café culture.

One of the capitals of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Budapest is one of Europe’s most important coffee and pastry cities. A quick trip down the Danube from Vienna, the origin of Sacher torte and namesake for all things croissant (i.e., Viennoiserie), Budapest holds its own when it comes to decadent pastries, having innovated Dobos torte, Esterhazytorte, Gerbeaud Cake, and perhaps, Kürtőskalács (kiortosh), a chimney/funnel cake popular throughout Hungary. Today, the most well-known Hungarian Jewish pastry is flódni, the de facto (and delicious), sweet propaganda aimed at tourists in “Judapest.”

However, flódni was not always queen. According to Koerner, in the nineteenth century, when flódni was principally eaten on Purim, the iconic Budapest Jewish pastry was bólesz, a Sephardic brioche evocative of a cinnamon roll. How a Sephardic pastry became central to nineteenth-century Budapest café culture is a story that begins 500 years ago when many Spanish and Portuguese Jews, fleeing the Inquisition, arrived in the Netherlands. Originally a fried, sweet dough ball in the Iberian Peninsula, the Sephardic bolas evolved into a baked, buttery pastry in the Netherlands. (Note that the Dutch do love their oliebollen, a fried dough ball that I suspect is a direct descendant of the Sephardic bolas, but I am not a Dutch culinary historian, so can only offer this suspicion.) In Sara Vos’ aforementioned inaugural Dutch Jewish cookbook, her bolas recipe dictates that these should be shaped as crescents and baked in an oven. While not exactly clear how (or when) bolas arrived in Buda’s kosher Café Herzl (which opened in the 1830s), or whether they were popular at other Hungarian Jewish cafés beforehand, Koerner’s research shows that these pastries were enjoyed in Jewish cafés throughout Hungary. Unfortunately, this pastry fell out of fashion in the 1930s and is now all but forgotten in Hungary.

Not only does Koerner tell us the story of this once-iconic pastry and other novelties from the Hungarian Jewish kitchen, but he offers both a historical recipe (1935) and a modern adaptation, albeit using dekagrams and other units less-familiar to American cooks. To learn more about “this wonderfully cinnamon-scented, soft-textured, easy-to-tear-apart” bólesz and 150 years of Hungarian Jewish cooking (in English!), I highly recommend you pick up this book. There are very few modern Hungarian culinary texts written in English, and even fewer translated by the authors themselves. To quote the title of Koerner’s recent exhibit of Hungarian Jewish foodways in Budapest, Jó Lesz a Bólesz—that is, “the bólesz will be good.” Andras Koerner’s work is a thoroughly critical and delightful preservation of Jewish culinary culture, food history, and recipes for all readers.

Avery Robinson is a Jewish culinary historian. He works in philanthropy and freelances as an editor, manages a rye bread company (Black Rooster Food), and has a climate change nonprofit, Rye Revival.