Philip Ball on winning the Wilkins-Bernal-Medawar Medal and Lecture

Philip Ball is the author of over 25 books, a writer, broadcaster, scientist, a longtime contributor and editor at Nature, and Marginalia’s contributing editor for Science. Philip Ball was recently awarded the The Royal Society’s Wilkins-Bernal-Medawar Medal and Lecture, which is given for “excellence in a subject relating to the history, philosophy or social function of science.” Here is our Editor-in-Chief, Samuel Loncar, in conversation with Philip Ball on this achievement:

SAMUEL LONCAR

Phil, can you tell us about this award and what it means to you?

PHILIP BALL

The Royal Society’s Wilkins-Bernal-Medawar Medal (and Lecture) is awarded for “excellence in a subject relating to the history, philosophy or social function of science.” It is named for John Wilkins, one of the founders of the Royal Society in the seventeenth century, the twentieth-century chemical physicist and crystallographer J. Desmond Bernal, who wrote extensively on the social functions of science, and the biologist Peter Medawar, one of the foremost scientific communicators in the latter part of that century. I have been awarded it “for outstanding commitments to sharing the social, cultural, and historical context of science through award-winning science communication in books, articles, and as a speaker and commentator.” Many of my books have been concerned with the historical and cultural contexts of science, and I imagine the citation encompasses also my broadcasting, especially my BBC radio series Science Stories, which presents episodes from the history of science.

It’s obviously a tremendous honor to receive this award from the UK’s principal scientific learned society. What makes it particularly gratifying is that it provides some recognition that the work I do manages, as I hope, to reach beyond science communication per se to provide contextualization. My work ranges from what one might call straight science reporting to commentary and critique of scientific issues. I’m particularly keen to set science within a wider historical, cultural, and philosophical context: to show where ideas come from, how they evolve, and how the cultures in which they arise influence the forms they take. To be honest, this can sometimes feel like a rather quixotic enterprise. The communication of science can sometimes become the kind of boosterish popularization that presents it as a sequence of amazing discoveries holding the promise of miracle cures, wonder materials, and utopian futures. Considerations of the broader social, political and philosophical implications are not always given much attention in the popular media; sometimes they are actively dismissed or avoided. So it’s tremendously validating to find that taking on that task – while it is certainly not the path to a bestseller! – is appreciated by some. The award reassures me that it’s worth the effort.

SAMUEL LONCAR

For those who aren’t aware of the truly extraordinary breadth and range of your work, could you tell us a short story about how you see the evolution of your writing and research, perhaps hitting on some of the major themes you see emerging in your books?

PHILIP BALL

I have always followed where my curiosity has led me, and have become increasingly less concerned about whether or not my books qualify as “science books.” I want them to be ideas books. For example, as someone who trained in statistical physics, I was intrigued to see the tools and concepts of that discipline (which is in itself not at all a widely popularized part of physics) being applied to social and economic systems in the early 2000s. My 2004 book Critical Mass explored that topic, and to do it justice I felt I needed to embed this modern work within the context provided by past philosophers, sociologists and political theorists who anticipated such idealized models of how human societies and institutions operate – people like Thomas Hobbes, John Stuart Mill, Karl Marx, and economists such as Paul Samuelson, Gary Becker and Thomas Schelling. I suppose it was the success of that book – it won the 2005 Royal Society Aventis Book Prize – that persuaded me that there was value in taking seriously what might be considered the extra-scientific content of scientific ideas and theories.

I’m very interested in how science interacts with the arts. My 2001 book Bright Earth looked at how the development of new pigments through chemical technologies from those of ancient Egypt to modern synthetic chemistry has affected the way artists use and relate to color. In The Music Instinct (2010) I looked at the cognition of music: how our brains make sense of music and respond to it emotionally and intellectually. Again I was very keen to tie this discussion closely to actual musical practice and experience across different times, cultures and genres. And my book The Self-Made Tapestry (1998), which looked at how patterns form in nature, has drawn great interest from artists of all sorts, with several of whom I have had delightful and fruitful further interactions.

I’m drawn towards cultural histories of concepts that intersect with science, the arts and literature, and society more widely. I see my books Unnatural (2011), Curiosity (2012) and Invisible (2014) as something of a trilogy, each of which examines how those notions have featured in the developments in science and technology, philosophy and the arts, and in our cultural narratives.

I’ve also published what might be regarded as more historical books, such as Universe of Stone (2008), an exploration of the building of the great Gothic cathedrals and the religious ideas that inspired them, and The Water Kingdom (2016), a view of Chinese history, philosophy, and culture from ancient times until today seen through China’s relationships to water.

I’m happy too to continue to write books that seem to sit more comfortably on the “popular science” shelves, such as my book on quantum mechanics, Beyond Weird (2018). As with all my books, the motivation for writing them is not simply to describe an interesting topic but to present a thesis – I need to have something to say about the topic, if I’m to write about it at all. In this case, Beyond Weird argues that it is time to discard many of the tired metaphors and analogies we science writers (and sometimes scientists) habitually employ to try to convey the non-intuitive nature of quantum physics. I believe that many of these tropes are misleading at best and sometimes plain wrong. I tried to suggest new ways of thinking about quantum mechanics that don’t rely on an appeal to weirdness. Even here, though – perhaps especially here – there is an irreducibly philosophical element to the issues that I think needs to be taken seriously as such.

SAMUEL LONCAR

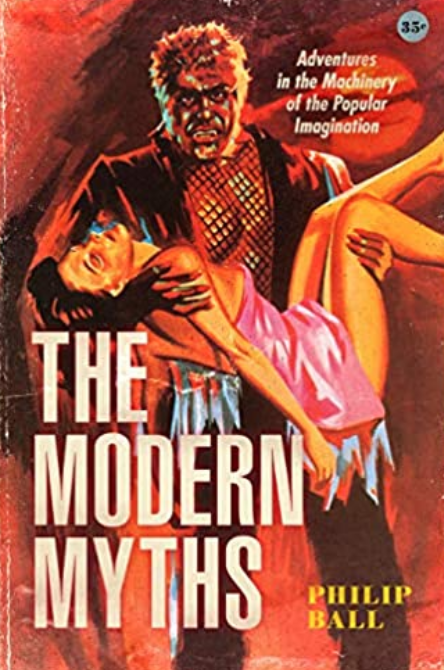

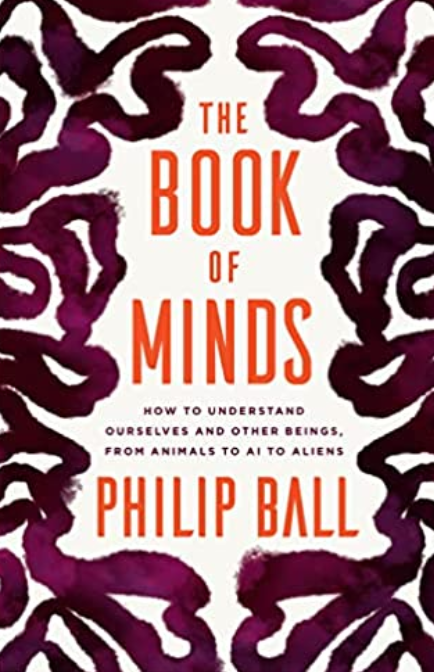

You’ve just published two major books: The Modern Myths and The Book of Minds. Both are different than normal books “about” science, the first dealing with the mythic character of modern culture, the second with what we might have in common with animals and, perhaps, even aliens.

Could you tell us a bit about these books and what effects you hope they have?

PHILIP BALL

The Myths book is something of an inevitable endpoint of some of those earlier books, especially Unnatural and Invisible – but perhaps it also goes right the way back to my 1999 book H2O: A Biography of Water. In writing those books, I had to recognize that topics and questions that seem scientific are in fact entangled with deeply rooted cultural beliefs and preconceptions. Often those ideas find expression in literary form: for Unnatural the Ur-text is Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, while for Invisible it is H. G. Wells’ The Invisible Man, which is itself a modern retelling of the legend of Gyges’ magic ring, recounted in Plato’s Republic. Both of those books are, I believe, modern myths. So I began thinking, well, what are our canonical modern myths – the stories told in the modern age (which I consider to have begun in the early modern period of the 17th-18th centuries) that serve the same roles that ancient myths have served? There is no definitive list, of course, but I selected seven “modern myths” that have often been casually labelled as such by literary critics – beginning with Robinson Crusoe (though I mention briefly that Don Quixote, which is even older, has a claim too), and taking in stories such as Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, Dracula, Wells’ The War of the Worlds, and Batman. I look at what these myths are about – which is never a single thing, for the vital feature of a myth is that it is mutable and can do different cultural work at different times. I was surprised at how consistent some of the attributes are – for example, the sketchy characterization, the loose and even chaotic plotting and structure, and the undertones of race, gender, and sexuality that have often been explored explicitly in recent retellings. At root, I believe that all these modern myths act as vehicles for exploring our anxieties, fears, dreams and obsessions. And they are all “modern” because their themes are ones created by modernity itself: colonialism, industrialization, urbanization, alienation, and very often the new possibilities of science and technology, such as artificial reproduction and space travel.

My hope is that the book will start a discussion: Which other stories are modern myths? Will they spring now from media other than literature, such as cinema (the newest nascent myth I consider is that of the zombie), graphic novels and comics, and the internet? How do these stories reconfigure our view of myth in general? (I found it interesting how much of the scholarship on mythology, especially in the early and mid 20th century, seemed intent on “othering” it: it was something that belonged to “pre-civilized” cultures, and which we in the rational developed world had left behind. This, I think, is utterly wrong.)

Out of all this too come some observations about literature itself: the roles of the fantastical and the breaking down of barriers between “literary” and “genre” fiction. These barriers have certainly become more porous in recent times, but I think we still have some way to go to acknowledge that the “mythic mode” in fiction does important cultural work that is quite distinct from the things we tend to celebrate, and to elevate, in what has conventionally been regarded as literary fiction.

The Modern Myths was, I should add, a labor of love – by which I mean in part that the publication process itself was hard work. Many editors didn’t know what to make of it, seemingly because they wanted to see me as a science writer. Others simply could not grasp the point, seeming determined to imagine that it was about urban myths or something. And some of the internal reviews obtained by my US publisher, presumably from academics, were downright weird: some wanted to insist that there could not be such a thing as a modern myth, others insisted that everything the book said was already well known. So it was rather gratifying that the book has just won an award from the Mythopoeic Society for the best scholarly work on myth and fantasy published last year.

The Book of Minds was published earlier this year, and is a survey of what we can currently say about what some researchers have called “the space of possible minds.” There have been intense and sometimes fractious debates recently about whether AI systems could ever have a mind in any meaningful sense, and whether perhaps they do already. We are belatedly waking up to the richness, diversity and often the subtlety of the minds of other animals. Some biologists and philosophers are now arguing that there is a case for considering plants to have minds; some even suggest that “mindedness”, in the sense of sentience or cognition, is a characteristic of every living organism. Questions about non-human minds are also central to the search for extraterrestrial intelligence – which, in truth, is often predicated on the idea that the extraterrestrials we’re looking for will be like us but smarter and with better technology. Is that a realistic assumption?

In my book I review all these ideas and try to provide some context for thinking about them in a way that is not irredeemably anthropocentric, by arguing that we can imagine a space of possible minds with many coordinate axes – sentience, say, and intelligence, memory, sensory modalities, and so on. Any thinking in this direction must so far be very preliminary and sketchy, not least because we still have a rather poor grasp of what many of these terms can and should mean – there’s no consensus, for example, on what consciousness is and how it arises in our own minds, let alone where else it might be found.

Perhaps this very lack of knowledge and consensus has tended to promote a degree of dogmatism in this field: there are countless books claiming to tell you what consciousness is or how our minds work. Many of these have very interesting things to say, but writing this book has made me more aware than ever that one of the pitfalls of science books written by experts is that they are often very partisan. They may present the author’s pet theory as though it is the only and the complete answer to a question on which there are in fact many other views. This doubtless sells books – it is great to be promised the answer to some deep scientific question. But I’m more interested in giving readers a sense of the diversity of views on a topic, and explaining their strengths and weaknesses. On hard questions like these, the honest answer is often that we know rather little – but that the journey we’re on is already a fascinating one.

SAMUEL LONCAR

You’re finishing a major book about the meaning of Life. Tell us what’s wrong with how we are thinking about life in science right now, and where you think the science is leading us.

PHILIP BALL

There are some books that I end up writing almost in spite of myself, almost with a dismayed voice in my head saying “What the heck do you think you are doing?” This tends to happen because I come to realize that the existing narrative offered to general readers (and even that exists sometimes within science itself) is no longer fit for purpose, and so there’s a job to be done to change it. My quantum book was of this nature, and so to some degree was my 2015 book Serving the Reich, which, by looking at how physicists in Germany responded to the Nazi regime, set out to challenge the complacency with which some scientists today continue to insist that what they do is “apolitical” and that social responsibility is someone else’s problem.

Well, this new book is one of these too. It is absurdly ambitious, in that what I’m seeking to do is to change the course of narratives about “how life works”: that’s to say, what this extraordinary process that makes and maintains entities like us truly consists of. Over the past two or three decades, the steady accumulation of knowledge within the life sciences has been remarkable, and I believe that it has slowly but surely shifted in significant measure the old picture that we are still taught at school and even at college. For example, one of the most valuable lessons from the Human Genome Project and the age of genomics that issued from it is that genes don’t really do what we thought they did. Or perhaps it is better to say, they do do what we have thought since the 1960s, which is to provide information for making proteins – but their causative role in life beyond that function is not quite what we imagined. Many proteins don’t work the way the textbooks say either; RNA is not simply the intermediary between DNA and proteins; cells are not really mere factories operated by genes; and so on. All these stories have changed. What emerges is a much richer, more versatile, less deterministic view of life. In particular we can now see that some of the notions that might work well enough for single-celled organisms like bacteria don’t really translate to complex, multicellular beings like us. What I came to conclude in writing the book was that the real shift, as we progress towards more complex forms of life, is in the nature of causation: it becomes ever less “bottom up”, dictated by genes and genomes, and much more hierarchical, for which a better metaphor than the machine or the factory is provided by cognition. We have never made a machine that works in the way life does, and it therefore needs to supply its own metaphors.

There’s a very curious phenomenon that I’ve noticed in the biological sciences, which is that shifts in the conceptual framework seem to get minimized with the comment that “we’ve always known that.” Whereas physicists seem to delight in saying “this changes everything!”, biologists seem almost embarrassed to admit that there’s a new story to tell. I have suspected this for a long time, but I have only acquired the courage, or maybe the foolhardiness, to attempt this book because of the three months that I was fortunate enough to spend in the summer of 2019 in the department of systems biology at Harvard Medical School. It’s a fabulous department, full of innovative thinkers. When I spoke to the folks there, time and time again they would not only agree that the old narratives about life are misleading or outdated, but they would often tell me “Oh, it’s much worse than that!” So this book is totally indebted to those conversations, and to the stimulus of removing myself from my habitual environment and thought patterns and being tipped into new modes of being. Of course, I’m not foolish enough to think that I now have all the answers to the many difficult puzzles about how life works, and I suspect that much of what I say in the book won’t quite pan out in the way I suggest. But again, I want to start the conversation about how to move biology along: how to bring to a wider audience the remarkable and exciting new insights that are often relegated to the black box between genes and organisms. It’s in that box that the real action now is!

SAMUEL LONCAR

If you could send a message to all young people interested in science, particularly to students who aren’t well represented in science today, what would you tell them?

PHILIP BALL

Science shares many of the problems of society more generally, such as discrimination and prejudice, a culture of excessive competitiveness and of unrealistic expectations, bullying, and vulnerability to assaults on democracy. But there is also much that is extremely hopeful and positive. At its best, the community of science is incredibly generous, open-minded and supportive. There is a genuine desire to confront and challenge the barriers that have existed for people of color and socioeconomically disadvantaged groups, for women, LGBTQ+ people, and people with disabilities. Grumblings from a few of the “old guard” about diversity initiatives are going to be ever less heeded. When change is impending, there will always be those who object, but that won’t prevent it from happening. I’m optimistic about this, although there is much work still to be done.

We have seen from the pandemic how vital science is for societies to thrive. I hope governments will have learnt not just that they need to support science in such times of crisis, but that only by sustained and committed support for basic research can we ever be equipped to navigate such challenging times. We have also seen how vulnerable science is to politically and ideologically motivated abuses and to misinformation: obviously again in the pandemic, but also in particular in climate science. But I am cautiously optimistic about that too, not least because I am involved in a group in the UK that is aiming to combat pseudoscience and misinformation, and so I have some notion of the innovation, commitment and wisdom that is going into such efforts.

SAMUEL LONCAR

Thank you so much for your time, and congratulations again on this beautiful recognition of your work. Any final thoughts you want to share with us, perhaps about new work or new ideas about science you wish more people were thinking about?

PHILIP BALL

Well, I have plans for future books – for perhaps four of them, to be honest. But those ideas need to grow in calm and seclusion right now.

During the pandemic, science became much more integrated into the cultural conversation – for better and worse, some might say. But I hope this can continue: that it ceases to be seen as an isolated and rather impenetrable sphere of activity and becomes regarded as one of the ways in which we humans exercise not just our ingenuity and curiosity but also our imagination. In the end, imagination is the key to so much of our potential. When we fail, it is often a failure of imagination. To make things better, we need to imagine it first.

_______________________________________

This interview is a part of the Meanings of Science Project.

Philip Ball is a scientist, writer, and a former Editor at the journal Nature. He has won numerous awards and has published more than twenty-five books, most recently The Book of Minds: How to Understand Ourselves and Other Beings, From Animals to Aliens, The Modern Myths: Adventures in the Machinery of the Popular Imagination and The Beauty of Chemistry: Art, Wonder, and Science. He writes on science for many magazines and journals internationally and is the contributing editor for Science at the Marginalia Review of Books. Tweets @philipcball

Samuel Loncar is a philosopher and writer, the Editor of the Marginalia Review of Books, the creator of the Becoming Human Project, and the Director of the Meanings of Science Project at Marginalia. His work focuses on integrating separated spaces, including philosophy, science and religion, and the academic-public divide. Learn more about Samuel’s writing, speaking, and teaching at www.samuelloncar.com. Tweets @samuelloncar

Read another conversation with Philip Ball in our Meanings of Science Project.